Over two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, many people continue to grapple with worsened mental health associated with social distancing, income loss, and death and illness. Roughly one-third (32%) of adults in the United States reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder in February 2022. Among these adults, 27% reported having unmet mental health care needs.

In this data note, we explore how the use of mental health care varied across populations reporting poor mental health before the pandemic using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in 2019. The 2019 NHIS data included detailed questions on symptoms of anxiety and depression. These questions were not asked on the 2020 survey, so pandemic-era NHIS data will not be available until the 2021 survey is released later this year.

In this analysis, we find that leading up to the pandemic, 8.5 million adults reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression but did not receive treatment either through therapy or prescription drugs in the past year. Among adults reporting moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, receipt of mental health treatment was lowest among several demographic groups – including young adults, Black adults, men, and uninsured people. These data provide a useful baseline for understanding disparities in mental health treatment that were already present before the pandemic, and may have been exacerbated by the public health crisis.

How many adults report symptoms of anxiety/depression and receipt of treatment overall?

Prior to the pandemic, nearly 1 in 4 adults (23% of people ages 18 and above) reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (Figure 1). Fourteen percent of adults reported mild symptoms of anxiety and/or depression while 5% reported moderate symptoms and 4% reported severe symptoms (Figure 1). In total, 54.9 million adults reported at least mild symptoms, with 9.5 million having severe symptoms. Anxiety and depression can affect quality of life and often co-occur with physical health problems.

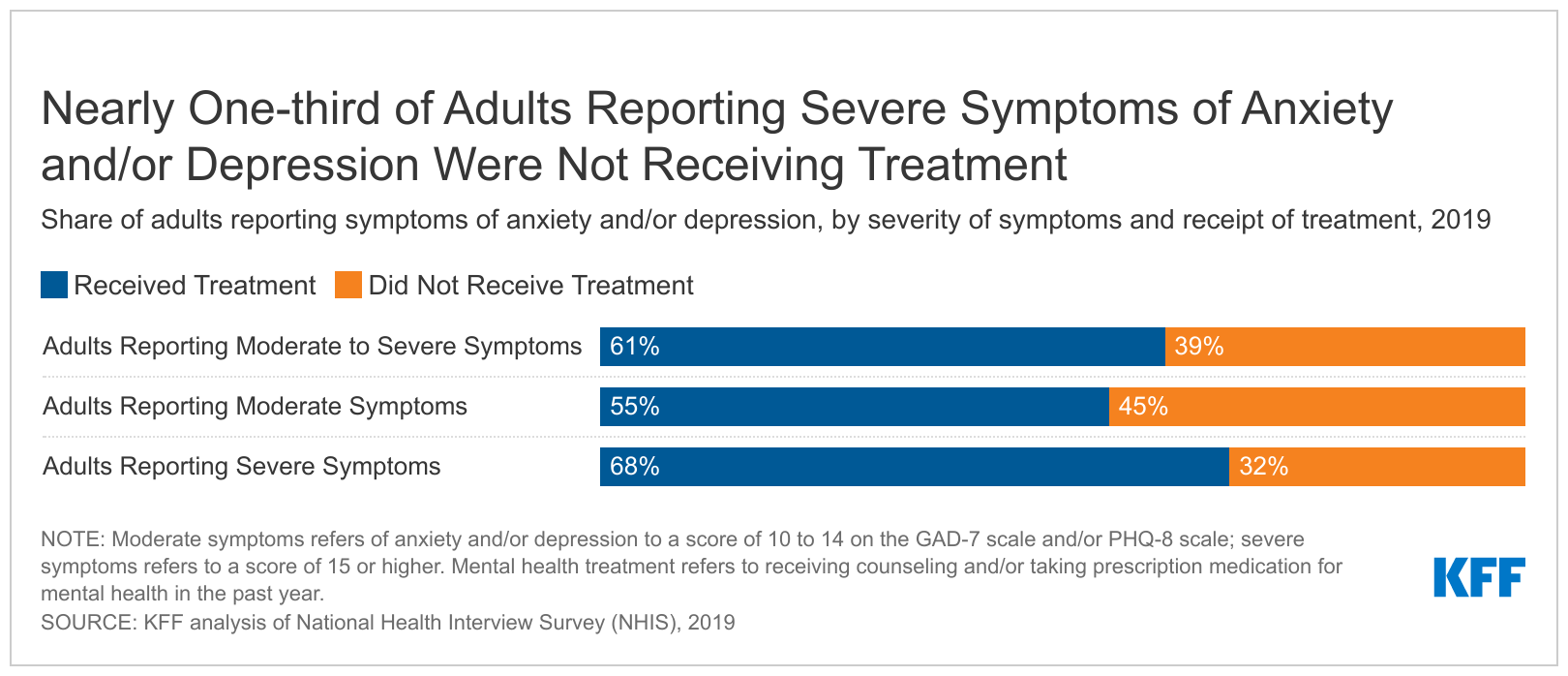

Many adults with mental health conditions do not receive care. In 2019, 21.6 million adults reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Among these adults, 8.5 million (39%) were not receiving treatment (Figure 2). Treatment is defined as receiving counseling and/or taking prescription medication for mental health, depression and/or anxiety in the past year. Among the 9.5 million adults reporting severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder, 3.1 million (32%) were not receiving treatment.

A number of factors may contribute to not receiving mental health care. Among those reporting symptoms of moderate or severe anxiety and/or depressive disorder, who were not receiving treatment, 23% indicated that they skipped or delayed therapy due to cost. Other data from 2019 found that among adults with any mental illness in the past year and unmet needs for mental health care, 25% cited not knowing where to obtain care as a reason they did not access services. Widespread mental health provider shortages coupled with low rates of insurance acceptance may also contribute to treatment barriers.

How does reporting of symptoms of anxiety/depression and receipt of treatment vary by demographic characteristics and insurance coverage?

The share of adults reporting moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression varied across some demographic groups and by insurance coverage. In 2019, more women (11%) than men (7%) reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (Figure 3). A disproportionate share of adults that reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression were enrolled in Medicaid (19%) and a smaller share are enrolled in an employer plan (6%).

How does receipt of mental health treatment vary by demographic characteristics and insurance coverage?

Leading up to the pandemic, disparities in receipt of mental health care existed across age, racial and ethnic groups, gender, and insurance status. In 2019, 10% of young adults (ages 18-26) reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorders, similar to older adults. More than half (55%) of these young adults reporting moderate or severe symptoms reported not receiving mental health treatment in the past year; this is significantly higher than the share of older adults reporting similar symptoms who were not receiving treatment (38% for ages 27-50; 32% for ages 51-64; and 38% for ages 65 and up) (Figure 4). Some research suggests that costs and factors associated with transitioning from pediatric to adult health care may be linked to limited mental health treatment among young adults in need of care.

In 2019, nine percent of White, nine percent of Black, and eight percent of Hispanic adults reported moderate or severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder. Despite substantively similar reporting of mental health symptoms across racial and ethnic groups, receipt of treatment varied considerably – compared to White adults (36%), a much larger share of Black adults (53%) with moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder did not receive treatment in the past year (Figure 5). In contrast, there was no significant difference in receipt of treatment between Hispanic and White adults. Data were not sufficient to conduct analyses for other racial groups. Research suggests that structural inequities may contribute to disparities in use of mental health care, including lack of health insurance coverage and financial and logistical barriers to accessing care. Moreover, lack of a diverse mental health care workforce, the absence of culturally informed treatment options, and stereotypes and discrimination associated with poor mental health may also contribute to limited mental health treatment among Black adults.

Men (7%) were less likely than women (11%) to report moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder prior to the pandemic (Figure 3). At the same time, men (47%) with moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder were more likely than women (35%) to not receive mental health treatment in the past year (Figure 6). Some research suggests men may be less likely to seek mental health care. Men are also more likely to be uninsured and less likely to report a usual source of care.

Uninsured adults with moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (62%) were significantly more likely to not receive mental health care compared to their insured counterparts (36%) in 2019. Narrow mental health networks in private insurance plans, including nongroup plans may be linked to access issues. Prior to the pandemic, individuals enrolled in nongroup plans commonly reported delayed or forgone care due to cost. Many employers have indicated that they have narrower provider networks for mental health services than other health care.

Despite having insurance coverage, insured adults with moderate or severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression and a usual source of outpatient care (57%) were more likely to not receive mental health treatment than those with a usual source of care (34%) in 2019 (Figure 8). Individuals with a usual source of care may receive mental health treatment directly or through referrals to specialized mental health treatment within or outside their usual care source. Having a usual source of care may improve but does not ensure mental health treatment. Irregular or no mental health screening in outpatient settings, difficulty finding or paying for mental health services, and coverage limitations may contribute to the lack of treatment, even among insured individuals who report a usual source of care.

How have mental health concerns and access to care changed since the pandemic?

An increasing share of people across the U.S. have reported poor mental health since the pandemic began. Some populations – including young adults and some communities of color – have fared worse during the pandemic. Higher shares of young adults reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depressive disorder, increased substance use, and thoughts of suicide compared to older adults. Mental distress and deaths due to drug overdose have also disproportionately increased among some adults of color compared to White adults. Additionally, Black and Hispanic adults have been more likely to experience negative financial impacts and higher rates of COVID-illness and death compared to White adults.

Barriers to accessing mental health care predate the pandemic, though they may have worsened in recent years, particularly for at-risk groups. Some steps have been taken to address challenges in accessing mental health care during the pandemic. Telehealth has played an important role in delivering mental health care during the pandemic. Restrictions around the use of telehealth and prescribing over telehealth were temporarily eased as were some state laws around provider licensing and practice authority. In 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act allocated some funds toward behavioral health workforce development and developing mental health mobile crisis support teams. Additionally, the national suicide hotline number, ‘988’, is set to launch in July 2022. There have also been some bipartisan efforts in response to the mental health crisis, including proposed mental health packages and a legislative agenda from the Addiction and Mental Health Task force. Recently, the Biden administration announced its Unity Agenda which proposes improving behavioral health workforce capacity, improving access to care in integrated settings, and expanding insurer coverage requirements. It is unclear how recent policy measures will impact access to mental health treatment especially among groups who experienced barriers to care even before the pandemic.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

| This analysis used data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a national probability survey of American Households sponsored annually by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The 2019 NHIS data included detailed questions on symptoms of anxiety and depression; these questions were not asked on the 2020 survey. This analysis uses full mental health screening scales (GAD-7 and PHQ-8). Other KFF analyses have used abbreviated mental health screening scales (GAD-2 and PHQ-2) in order to draw comparisons to estimates from the Household Pulse Survey during the pandemic. Abbreviated mental health screening scales flag individuals with moderate or severe symptoms aligned with a diagnosable condition, whereas the full screening scales shown in this analysis categorize mental health symptoms into mild, moderate, or severe groups. This analysis includes data on White, Black, and Hispanic adults. Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race but are categorized as Hispanic for this analysis; other groups are non-Hispanic. Data were insufficient to allow for analysis of other racial groups. Respondents may report having more than one type of coverage; however, individuals are sorted into only one category of insurance coverage. We define individuals in treatment as those who received counseling or therapy from mental health professional in the past 12 months, or someone taking a depression, anxiety or mental health prescription drug. |

"use" - Google News

March 24, 2022 at 10:01PM

https://ift.tt/0msgrX9

How Does Use of Mental Health Care Vary by Demographics and Health Insurance Coverage? - Kaiser Family Foundation

"use" - Google News

https://ift.tt/kaHQOBd

https://ift.tt/Tx3n4HO

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How Does Use of Mental Health Care Vary by Demographics and Health Insurance Coverage? - Kaiser Family Foundation"

Post a Comment