The Trump administration’s decision to execute five condemned federal prisoners during the presidential transition, an unprecedented killing spree, stems from the same blunt theory of governance that saw Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refuse to hold a Supreme Court confirmation hearing for Merrick Garland during the 2016 election while rushing to confirm Amy Coney Barrett even deeper into the 2020 one. In each instance, those with power eschewed cherished norms and political comity to rawly exercise it Their right to do these things gave them the might to do it.

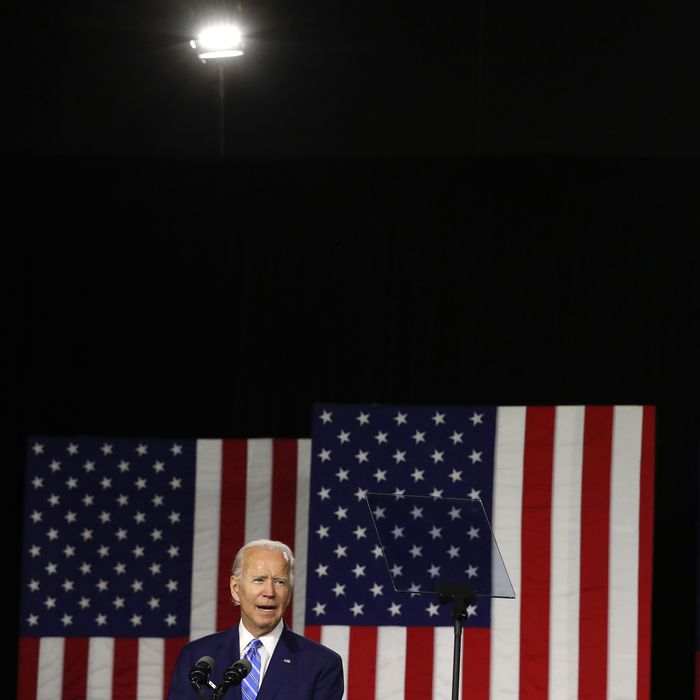

In a little over four weeks, Joe Biden will have that same power to write his own history with capital punishment in America. The central question now is whether he has the political will and moral strength to exercise it. He can empty federal death row in Terre Haute, Indiana, by commuting to life-without-parole terms the death sentences of the 50 or so people left on it. He can direct the Justice Department to instruct each and every U.S. Attorney around the country not to pursue capital charges for federal crimes. He can order the completion of the death-penalty study left unfinished by Obama administration officials, who talked briefly about a moratorium on the federal death penalty but then abandoned the idea.

There is Democratic support for such bold moves. Forty members of Congress just sent Biden an open letter urging him to power down what the late justice Harry Blackmun once called “the machinery of death” so that future presidents cannot do what Trump has done — execute more people this year at the federal level than were executed during the same period in all states with capital punishment combined. Biden cannot forever limit future presidents from authorizing federal death sentences or putting people to death — only the U.S. Supreme Court or Congress could do that — but he can make it measurably more difficult for the next authoritarian to build up a new federal death row.

Biden’s views on the death penalty have evolved over the past three decades, as have many of his other views on crime and punishment. In the early 1990s, in the run-up to Congress’s passage of the infamous 1994 crime bill he co-authored, Biden supported more opportunities for capital punishment as part of a brutal sentencing regime that added dozens of new crimes to the litany of those for which the death penalty was an option. He’s smarter now, he says. A few years ago, as he mulled a presidential run, and as the toll of the 1994 law became too much to bear, Biden began to change his tune and soften his stance. Now, he says he’s opposed to capital punishment and is ready to do something about it.

The next president ought to cite the current president’s unseemly rush to kill the condemned as final proof that meaningful change must come to our capital punishment systems. Biden ought to cite, in particular, the fact that the Trump administration has proceeded with its executions even as the coronavirus swirled around federal death row, endangering the lives of federal employees. For if the Trump administration has established anything with its execution spree these past few weeks — if we have learned anything from the end of a 17-year moratorium on federal executions that spanned three administrations — it is that the federal death penalty is in many ways as broken as are the capital laws and policies in states where executions are carried out year after year.

The Trump administration selected for execution those federal-death-row prisoners whose crimes officials considered especially heinous. Lisa Montgomery, for example, who is scheduled to die next month, killed a pregnant woman and then carved the baby (which miraculously survived) out of her stomach the baby. But Montgomery herself was a victim of serial sexual abuse starting when she was just a child. Alfred Bourgeois, killed last week by lethal injection, committed his crime two decades ago at age 18, when he was part of a carjacking crew that suddenly turned murderous. His attorneys tried for years to convince a judge that he suffered from intellectual disability. The crimes for which capital punishment is prescribed are almost always simple to explain. The backstories of the people who commit them are almost always nuanced and complex. “Each person is more than the worst thing they’ve ever done,” the great justice advocate Bryan Stevenson loves to say.

For every sentence Attorney General William Barr has uttered about the depravity of the capital crimes that land people on death row, there is a story like this one about Brandon Bernard, who was executed earlier this month amid questions of flaws in his long-ago trial: racial bias in jury selection, ineffective assistance of counsel, the failure of judges and jurors to hear or appreciate evidence of mental illness, intellectual disabilities that undermine intent, police and prosecutorial misconduct, unreasonable procedural hurdles. These eternal problems, which undermine the confidence we all should have in capital convictions and sentences, crop up over and over again in death penalty cases and will continue to do so until (and unless) legislators properly fund capital defense work and judges adequately recognize and defend the constitutional rights of capital defendants.

That financial relief and jurisprudential rescue isn’t around the corner even though some states recently have repealed the death penalty. So what I want to know, as we prepare for the inauguration next month, is something that is unknowable to those of us who are not part of Biden’s inner circle. Does Team Biden believe that death-penalty reform is a winning political move or not? Is he willing to exercise the power he has to abolish or limit the federal death penalty, regardless of the political price that Democrats may pay in upcoming elections? Or does Biden believe that the arguments against capital punishment today are so obvious and reasonable (and ultimately popular) that the predicable Republican attacks that would follow his reforms wouldn’t gain traction?

Remember that we are in the middle of a debate within the Democratic Party over whether progressive support for the poorly named “defund the police” movement actually cost Democrats seats in the House in 2020. Biden himself suggested as much a few weeks ago. It is easy to predict that a Biden-administration move to empty federal death row, for example, would immediately be met by blunt criticism from the law-enforcement lobby and other proponents of capital punishment. Those members of Congress pressing Biden over capital punishment surely know that any meaningful reform he brings will come up on the campaign trail in purple districts in 2022.

If Biden acts boldly, the subsequent debate will not be hard to imagine. The still-vibrant death-penalty lobby will try to portray the act as a step toward lawlessness, the elimination of a vital layer of protection for law-abiding citizens just as murder rates are beginning to tick up again from generational lows. That this reasoning is bunk makes it no less potent for some. It does not matter that the deterrence argument for capital punishment has long since been discredited or that the racial and geographic disparities in the administration of the death penalty render it fatally flawed. Who gets executed, and who does not, mainly depends on where murders take place, the race of the victim, and the sensibilities of the local prosecutor and judge. The very essence of the fear-of-fear-itself movement is to eschew facts and evidence.

I would love to be inside the room as senior Biden administration officials run the moral imperative of stopping or restricting a barbaric practice through the political calculus such a move would entail. Is growing conservative support for the abolition of the death penalty enough to offset the potential political downside of capital-punishment reform in close congressional districts? Does it matter anymore what genuine conservatives think about the death penalty so long as Donald Trump favors it? What if the Biden team abolishes the federal death penalty, and the Democrats lose control of the House in 2022 — would the death penalty be blamed as a reason?

Biden has the power to do something here that Barack Obama failed or refused to do when he had the presidency. He has the executive authority to put to right what we all have seen Trump and Barr help break — a system of capital punishment that, during a pandemic, could amount to a death sentence for guards, witnesses, and others as well. Whether Biden decides to exercise this power, to spend this political capital in this fashion, will likely provide us with an early look at the way he’ll approach the post-Trump era more generally. For the condemned on federal death row killed by lethal injection during the Trump era, the change won’t come in time. For those who remain on death row, the reform can’t come soon enough.

A version of this article appeared at the Brennan Center for Justice.

Note: Changes to the Full-Text RSS free service

"use" - Google News

December 23, 2020 at 04:04AM

https://ift.tt/3h9YlFn

Will Biden Use His Powers to Crush the Death Penalty? - New York Magazine

"use" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2P05tHQ

https://ift.tt/2YCP29R

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Will Biden Use His Powers to Crush the Death Penalty? - New York Magazine"

Post a Comment