Then there are the doomsayers. To them, the world was already on a cliff edge in 2019. Globalization had been in retreat, productivity stagnant, and spending squeezed. The lessons of the 2008 financial crisis had not been learned. The coronavirus, in this view, is now pushing us over the edge, into a downward spiral of recession, mass unemployment, collapsing demand, poverty, conflict, and war.

Finally, there are the alternative optimists. To them, the crisis will pull down consumer capitalism but, luckily, in its place bring forth a nirvana of greater self-sufficiency, environmental stewardship, and social justice. Finally, the air is clean and the birds are singing. Lockdown, in this view, is shaking people out of their materialist slumber, exposing all the “false needs” they had been brainwashed into, and teaching them to focus on their “real” needs instead: health, family and friendship, and baking bread. This view, it is worth noting, is not limited to environmentalists, critics of neoliberalism, and disciples of simple living. It is shared by some retail analysts. “If I sat here for the last three months,” one British consultant said, “and I haven’t bought a new pair of shoes or a handbag, maybe it wasn’t as important as I thought it was?”

What is clear is that we are dealing with an unprecedented crisis. At the time of writing, almost all rich societies have had a taste of lockdown. In addition to the initial countermeasures taken to slow the spread of contagion, and flatten the pandemic’s curve of lethal exposure, there will be a second and, perhaps, third wave of the virus to worry about. People have flocked to parks and beaches and joined protest marches. Still, all countries that have come out of lockdown continue to have various restrictions in place, from limiting numbers in bars and entertainment venues to the prohibition of group sport and leisure. Scientists have warned that some physical distancing measures may need to remain in effect until 2022. Even Sweden and South Korea, which allowed shops and restaurants to stay open in spring, have not been able to escape commercial meltdown. Fewer people eat out in South Korea today than last year, and a sudden rise in the number of infections prompted a shutdown of bars in early May. Shopping malls in Stockholm are half empty; H&M sales fell by half in Denmark and Finland, but even in Sweden, without a lockdown, they dropped by a third.

Wherever we look, figures and forecasts are getting more dire by the day. In the first quarter of 2020, the U.S. economy shrank by 4.8 percent, and 30 million filed for unemployment benefits between mid-March and early May. Spain is suffering the biggest recession since the Civil War (1936–39). Germany and Switzerland predict a 6 to 7 percent drop in GDP for the year. When I started this article in the middle of April, British forecasts were for a 6 percent drop in GDP. In early May, the Bank of England published its scenario that put it at 14 percent. This would be the worst recession the nation of shopkeepers has suffered for three centuries; by comparison, in the 2009 financial crisis, the British economy contracted by 4 percent. In Britain, a quarter of the workforce has been laid off; one million people applied for social benefits (Universal Credit) in the last two weeks of March alone. American and British estimates predict that consumption will drop by 15 percent this year, and some analysts think even that might be optimistic.

What makes the coronavirus so disruptive is not so much that it will take a few thousand dollars out of the pocket of the average customer this year; rather, it’s shaking the foundations on which modern consumer culture has been built over the last 500 years. The imperial trade in exotic goods, the lure of novelty and fashion, the expansion of comfort and convenience, and our accumulation and ever-faster replacement of possessions have been the result of a dynamic exchange between the local and global, the home and the city, public and private. Bright, colorful cotton from India; porcelain cups from China; sugar, coffee, and cocoa from the Caribbean and Latin America; curtains and carpets, the tea party and coffeehouses, urban arcades, pleasure gardens, cinemas, and department stores—all of these depended on the joint movement of goods, people, and tastes. The Bon Marché, Selfridges, and other department stores around 1900 were not entirely revolutionary, but one practice they introduced proved critical to the later consolidation of a culture of consumption: the simple act of letting customers touch the merchandise. Contemporaries compared them to ocean liners—and that is, of course, precisely why some have remained closed and, in several cases, will stay closed forever.

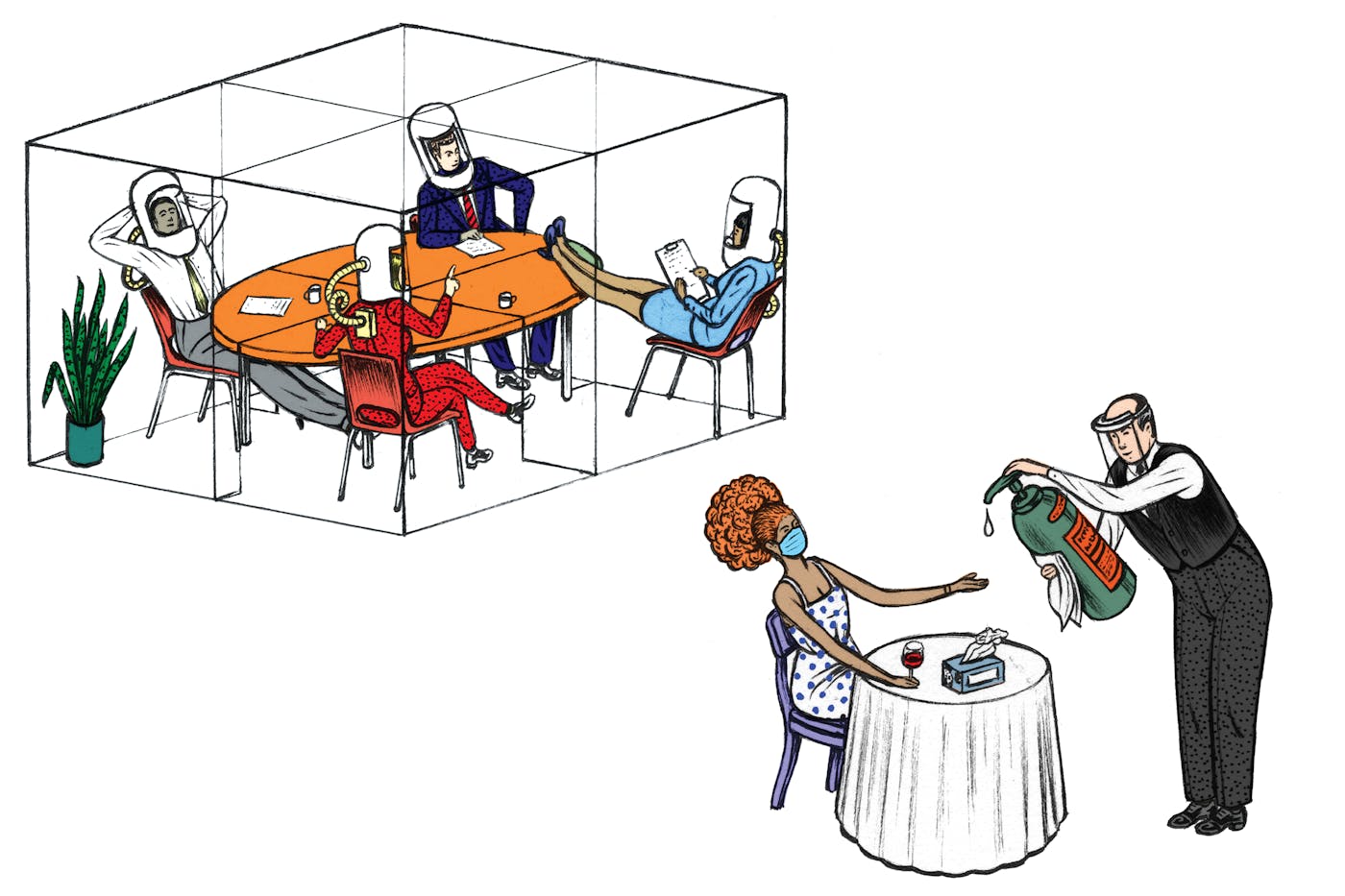

The virus has effectively stopped several pistons of consumer economy at once. Tourism and mobility, restaurants and retail, live entertainment and sports: Each of these is a big sector in its own right, but together they are enormous. In the United States, 6 percent of total consumer spending is on restaurants and hotels alone, and another 4 percent goes to recreation. Italy, Austria, and Spain each make about 14 percent of their GDP from tourism, Greece as much as 20 percent. Retail experts forecast that 20,600 British stores (with a quarter of a million jobs) will have closed their doors by Christmas. Germany has some 70,000 hotels and restaurants. How many of these will survive the crisis? In Germany, some theaters are reopening, but with only half the seats. Sporting events are gradually resuming, but behind closed doors. Broadway is not expected to reopen until 2021.

What makes the virus so damaging is its synchronized effect on activities that mutually depend on mobility and proximity. Fewer tourists and business travelers translate into fewer hotel and restaurant guests and fewer visitors to shops, special exhibitions, concert halls, and musicals. Take the cruise, for example. Cruises took off 30 years ago. Last year, 30 million passengers sailed the seas. They generated $68 billion in direct expenditure where they docked—spending on excursions, trinkets, and shopping, along with all the food and drink and supplies bought for the ships. The Mediterranean and Baltic routes are now almost as popular as the Caribbean. Half a million passengers embarked last year in the Finnish capital of Helsinki, which has just over one million inhabitants. The MSC Meraviglia alone carries 4,500 passengers to Norway. You can argue whether the 15-deck, 315-meter–long behemoth deserves its name (“Wonder”), and cruises and airplanes carrying package tourists are big polluters. Still, the spectacular new music halls, arts festivals, and restaurants that have regenerated many Nordic cities are inconceivable without them.

When we think about the future of demand, though, we need to ask about its quality as well as quantity. What is all the demand made up of that we are so worried about? And how is life during and after lockdown changing the activities that result in demand? These may appear straightforward questions, but they are ones that economists and policymakers have been finding very hard to get their heads around. Many simply assume that we will “rebound” and gradually resume our lives more or less where we stopped before lockdown—as if the experience of isolation and ongoing distancing will not change how we consume (and what we “demand”) at all. At most, they assume that it will take a few months for people to flock back to restaurants. This is an extremely narrow view of consumers and how they lead their daily lives: All eyes are on the money in people’s pockets and how much makes it into the cash register. But consumption is not simply a reflection of how much money there is to spend. We need to know why people turn to certain goods and services in the first place. And disruption changes that.

"consumption" - Google News

August 10, 2020 at 05:02PM

https://ift.tt/3kwNFlx

The Unequal Future of Consumption - The New Republic

"consumption" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2WkKCBC

https://ift.tt/2YCP29R

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Unequal Future of Consumption - The New Republic"

Post a Comment