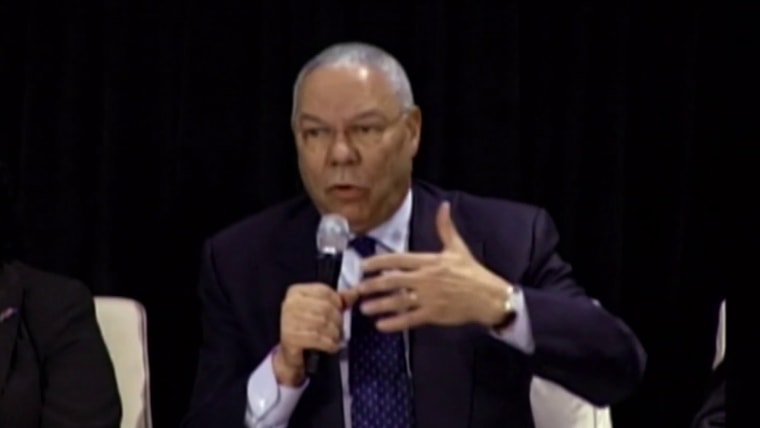

WASHINGTON — When he exercised it — in the realms of foreign policy, national security and politics — discretion was the better part of valor for Colin Powell.

In the summer of 1992, President George H.W. Bush's re-election campaign commissioned a secret poll to see whether Vice President Dan Quayle should be dumped from the Republican ticket, and, if so, who should replace him.

Some of Bush's closest advisers hoped to sub in Colin Powell, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the architect of the highly successful U.S. invasions of Panama and Iraq. Powell polled better than Quayle and Secretary of State James Baker but "wanted no part" of displacing the sitting vice president, Baker biographers Peter Baker (no relation) and Susan Glasser wrote.

Powell would later turn down entreaties to run for president in 1996 and in subsequent election years. His decision to steer clear of elective office cost Powell a chance at greater power. But it cemented his legacy in Washington as a soldier, public servant and statesman who could put his country above personal ambition and partisan politics, and it gave him credibility as he worked — with mixed success — to shape modern American national security and foreign policy.

It was that legacy, and a philosophy that emphasized both a strong military and a reluctance to use it, that won Powell praise from across the political spectrum when he died Monday at 84.

"General Colin Powell was a patriot: serving our country in uniform, leading at the highest levels of American government and blazing a trail for generations to come," Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., said in a statement. "His leadership strengthened America and his life embodied the American Dream."

The New York-born son of Jamaican immigrants, Powell entered the military through the Reserve Officer Training Corps program and served two tours in Vietnam. Over the course of the next few decades, he ascended the ranks to become a four-star general, serve as a top aide to Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, and take over as President Ronald Reagan's national security adviser in the wake of the Iran/Contra scandal.

Powell was the first Black person to hold that post, and he would later become the first Black chairman of the joint chiefs, under Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, and secretary of state, under President George W. Bush.

After his experience with America's failure in Vietnam, and with the Cold War coming to a close during his time as national security adviser and joint chiefs chairman, Powell developed an eight-part test for the U.S. use of military force. Known colloquially as "the Powell doctrine," it is predicated on going to war only when other forms of influence have been exhausted and the U.S. can identify an achievable mission that enjoys domestic and international support.

His theory would come to define the limited use of American military force for more than a decade. Powell would oversee the defeat and capture of Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega in a brief invasion that ended in January 1990, as well as Desert Storm, the 1991 U.S. invasion that led Iraq to withdraw its forces from Kuwait. Powell's approach would also inform Bush's and Clinton's refusal to commit ground forces in various theaters. In particular, Powell vocally and successfully argued against putting troops in the Balkans following the fall of Yugoslavia.

The era of the Powell doctrine would come to an end, perhaps ironically, when he took his most prestigious posting, as secretary of state, in January 2001. Powell was outnumbered by more hawkish members of the Bush administration, including Vice President Dick Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who worked to push him out of the national security loop.

His philosophy was fully shelved following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Powell supported Bush's invasion of Afghanistan but he was alarmed by the hawks' push to go to war in Iraq the following year.

Powell sought an audience with Bush and was invited to dinner with the president and national security adviser Condoleezza Rice at the White House residence in early August 2002. Powell warned Bush about the difficulties and consequences of an invasion.

"You are going to be the proud owner of 25 million people," Powell said, according to Bob Woodward's book "Plan of Attack." "You will own all their hopes, aspirations and problems. You'll own it all."

Powell went on to advise that Bush take his case to the United Nations in order to lock down international support, knowing that failure to get it could mean averting a war, Woodward reported. He stopped short of recommending against an invasion.

And on Feb. 5, 2003, Powell went to the U.N. to prosecute the case for war.

"Saddam Hussein and his regime are concealing their efforts to produce more weapons of mass destruction," Powell said during a presentation in which he famously held up a vial of what he said could be a biological weapon. He would later express regret about the deceptive presentation — Hussein had no chemical, biological or nuclear weapons. The evidence Powell repeatedly termed solid was anything but.

While the presentation did not move the U.N. Security Council to back the U.S., Powell was influential with his real audience: members of Congress, the media and the American public. His stamp of approval was persuasive for some.

"Secretary Powell made a very powerful, and I think irrefutable, case today before the Security Council," then-Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, who is now the president, said at the time. "The evidence he produced confirms what I believe and I have known for some time now: Saddam Hussein continues to — he continues to attempt to maintain and garner additional weapons of mass destruction, and he continues to thwart the world's command, through the United Nations, to disarm."

Powell would leave public service in 2005, re-appearing in the spotlight from time to time. In 2008, he endorsed Democrat Barack Obama over his longtime friend Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., and, in 2020, he endorsed Biden over President Donald Trump. Powell left the Republican Party to become a political independent earlier this year.

Journalists sought his views on politics because he knew the players and the debates, and because he was well regarded by the American public. That sentiment was shared by political elites.

"He was such a favorite of presidents that he earned the Presidential Medal of Freedom — twice," George W. Bush and former first lady Laura Bush said in a statement Monday offering condolences to Powell's family.

Powell was rewarded for his caution — when he used it.

"use" - Google News

October 19, 2021 at 03:42AM

https://ift.tt/3jchubK

Powell's discretion heightened his credibility — when he chose to use his power - NBC News

"use" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2P05tHQ

https://ift.tt/2YCP29R

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Powell's discretion heightened his credibility — when he chose to use his power - NBC News"

Post a Comment